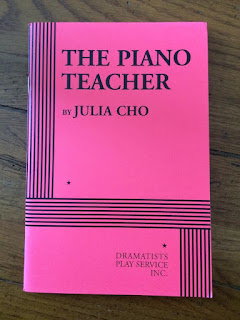

The

Piano Teacher by Julia Cho

Production,

11-5-18, 4 pm, The Kitchen Theater

Directed by Diego

Arciniegas

And it came through two of her

students. The first was a young woman, Mary Fields, played by Amelia Windom, who

let her former teacher know something was truly not right in Mrs. K’s house.

The piano lessons weren’t the only lessons being learned and what was taken in

was more than the students and the teacher were there for. It was going on with

Mr. K as they waited for their piano lessons. But Mary Fields let Mrs. K know

this within acceptable perimeters of social efficacy—compassion for an lonely,

old woman. It also prepares us (or sets us up) for what follows.

The second student was one with

great musical potential, Michael, played by Matthew J. Harris, but who hadn’t

reached the fulfillment of that promise. He seems to appear out of nowhere,

like a sudden threatening storm, who reveals that what he had hoped for when he

was young had been turned on end by circumstances beyond his control,

influences which had warped his chances of becoming who he could have been. Or

had he been inherently attracted to that which stole his youth, hope and

promise? Is he an expression of a highly disturbed old man, Mr. K’s psyche

after what actually happened to him during the war or is Michael a repository

of atrocious stories to which he’s been attracted, even a potential sociopathic

killer now on the brink of a spree. Whether any or all of these, he definitely has

come to believe that he’s that which corrupted and defiled him in Mr. and Mrs.

K’s house from the stories Mr. K tells him about his destroyed youth, the only

survivor of a town of innocents slaughtered by the Nazis and Mrs. K’s supposed

innocence to what is happening in her kitchen.

The genius of the play is how

seamlessly I was catapulted from a living room conversation into a submersion

of an unblinkingly brutal experience with evil. It was like having a coffee

klatch with Ted Bundy’s wife who claimed her husband wasn’t really slaughtering

the innocent because of the derangement done to him. How much did she know and

hide? How much did she not care to know, ever know, about her husband’s made-up

stories that symbolized the real murders?

The play is a tumble of layer upon

layer of guilt repression, hidden secrets and terrible memories which fills us

who watch (much like Mrs. K and her TV watching), with fascination at what the

world gives us to see and hear but in which we find ourselves helplessly stuck

as to what to do with what we’ve learned. I walked out of the theater with

questions that followed me into my living room later, when I reached for the television

clicker that turned on the nightly news—which could have just as easily been my

computer and any number of news venues at my fingertips.

What happens when we do not face the

monsters we have created in both our interior and exterior worlds? What do we

think we are doing when we make these territorial wars that place us in the

middle of atrocities that we are not equipped to handle, let alone endure, but

we take on in order to survive? And then what do we do when we have no models

or guides for life after the survival? What do we do when we are silent

witnesses to our created monsters that live on within and without? What do we

do with the dragon that fuels our imaginations and creative art? Do we fight

the demons? Sit with them? Keep them from overtaking us through make-believe?

Fairy tales? Television shows? Movies and the stories we tell each other over

daily coffees?

These questions sound like the ones

a screenwriter might ask while creating a script for a Gonzilla or Jurassic

Park movie. But The Piano Teacher

shows us clearly that ordinary life is filled with just such monstrosities that

do breed demons within. It is a story of every man and woman who lives today,

who sit and watch the news on television and don’t know, perhaps don’t care to

know what to do with the information of eighteen thousand murders that occur

each year in our society as both entertainment and reality.* What do we do with

the knowledge of all the atrocities everywhere?

The America we live in is no haven

from atrocities elsewhere. Atrocity dwells in any place we live without

awareness and truth and the will to act against it. And herein lies the

dilemma. To work to eradicate it means a never ending battle that takes us from

our ordinary lives, our personal desires and goals, our comfort zone, but

without balance our resistance can eat us alive. It’s why, in the end, when

Mrs. K. faces us with her resolve, we can’t with self-justified correctness

tell ourselves we fight the good fight and aren’t anything like her. We are

like her, but not only her. In this play we come to know that we are convincingly,

horrifyingly like them all—each and every one.

*17,250 murders in the U.S. in 2016;

around 11,750 violent acts witnessed on television each year by age 17.

No comments:

Post a Comment